Average Household Expenditures by Major Category Family of 4

Household Expenditures and Income

© Getty Images

© Getty Images

Overview

Expenditures are a key only often disregarded element of family balance sheets. In measuring household financial security, significant attention is typically paid to income, merely much less to whether those resources are sufficient to encompass expenses. To begin addressing this gap in the policy discourse, this chartbook uses the Bureau of Labor Statistics' Consumer Expenditure Survey to explore household expenditures, examining changes in overall spending and across individual categories from 1996 to 2014.1 It as well details the differences in expenditures by income, with a detail focus on the degree to which households have slack in their budgets that could exist devoted to savings and other wealth-building efforts.

This analysis focuses on the working-age population, which includes survey respondents or their spouses who are between the ages of 20 and 60. For the purpose of examining differences in spending by income, the sample was divided into thirds.

The analysis shows that both median income and expenditures contracted subsequently the Great Recession, reflecting the economic turmoil of the land. By examining household spending, this research helps to shed light on family financial security over time, and specially in contempo years. Key findings include:

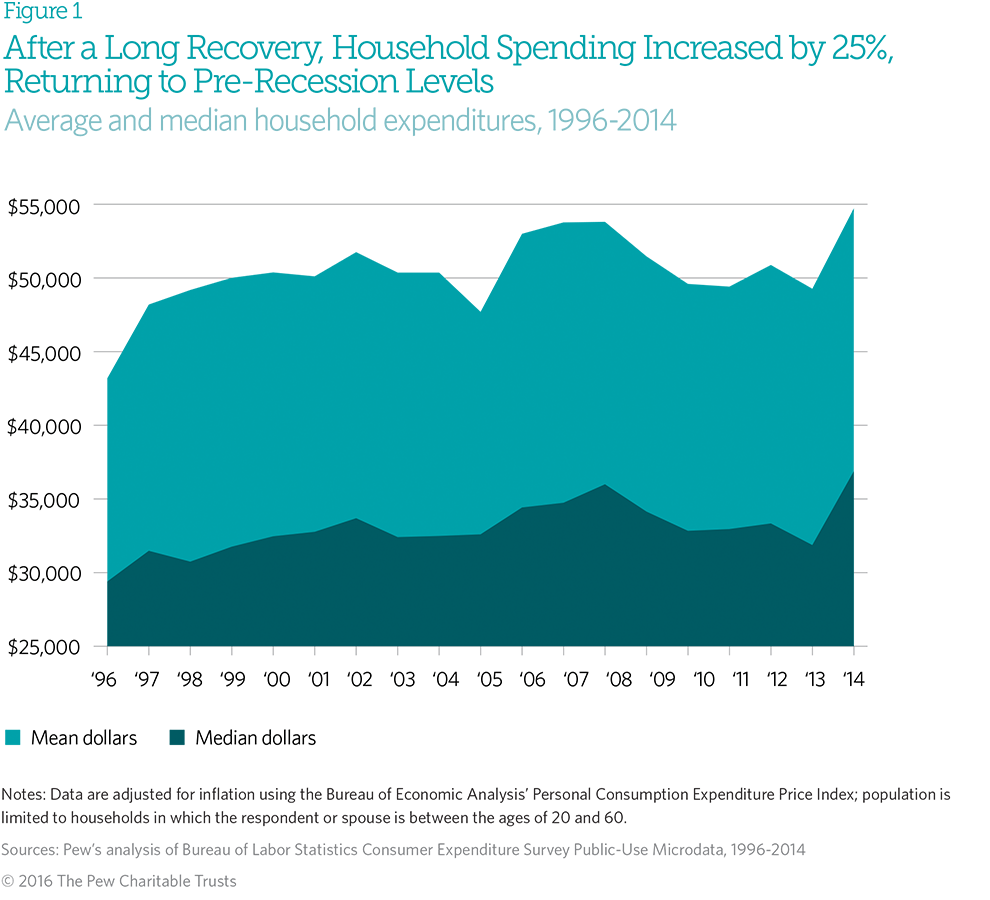

- Overall median household expenditures grew by almost 25 percent between 1996 and 2014, returning to pre-recession levels. 2 After declining during and later on the Great Recession, expenditures increased betwixt 2013 and 2022 in particular. In 2014, the typical American household spent $36,800.

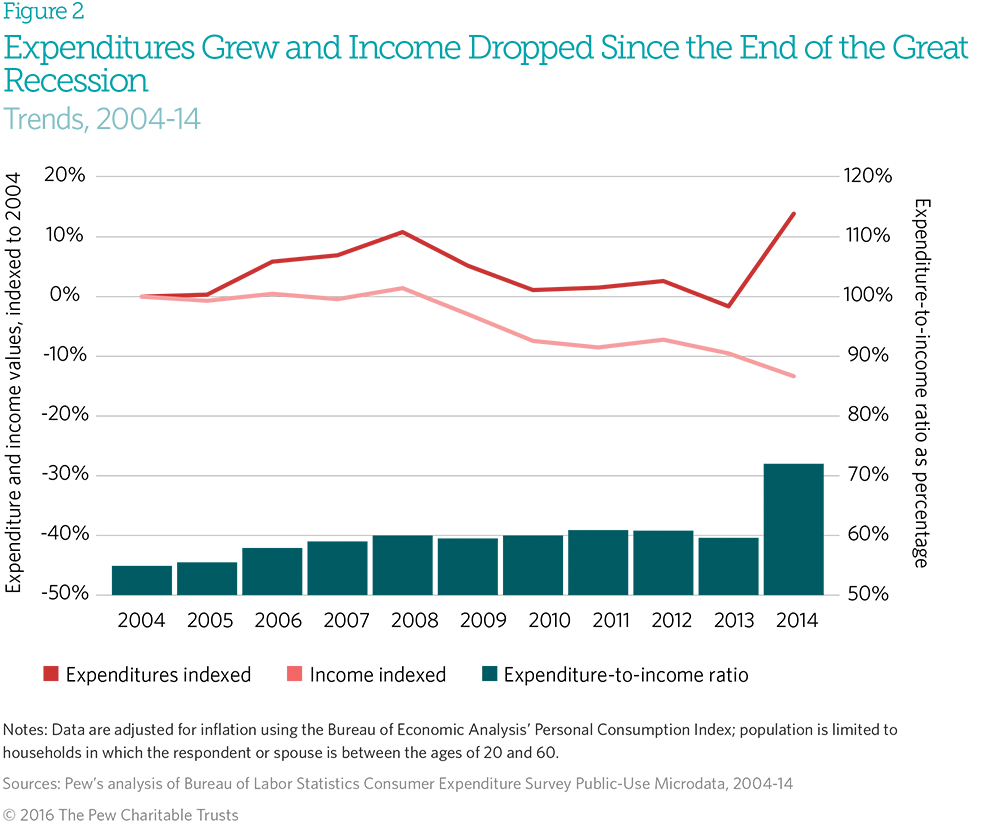

- Although expenditures recovered from the downturn, income did not. Every bit the recovery began, median household expenditures returned to pre-crisis levels, just median household income continued to contract. By 2014, median income had fallen by thirteen percent from 2004 levels, while expenditures had increased past about 14 percent.

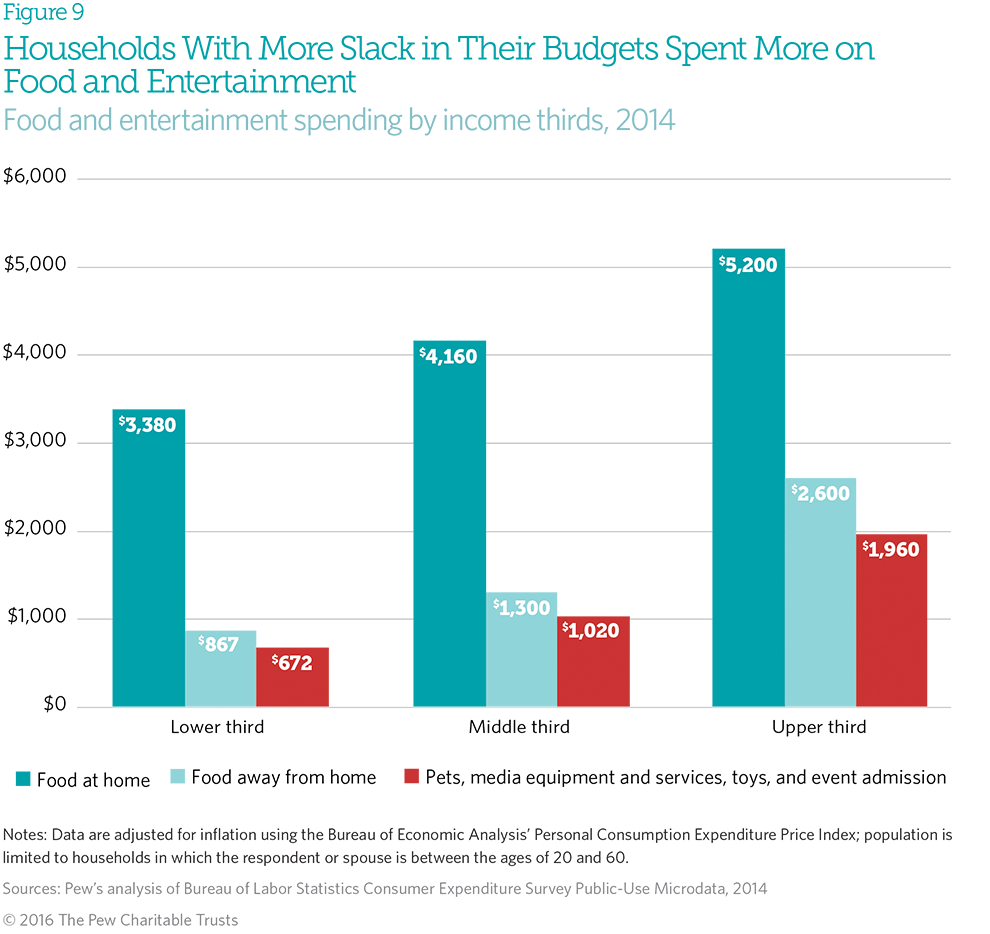

- Low-income families spent a far greater share of their income on core needs, such as housing, transportation, and food, than did upper-income families. Households in the lower third spent 40 pct of their income on housing, while renters in that 3rd spent nearly half of their income on housing, as of 2014. Because their core spending absorbed so much of their income, households in the lower income tier spent considerably less than their center- and upper-income counterparts on discretionary items, such as food away from home and entertainment.

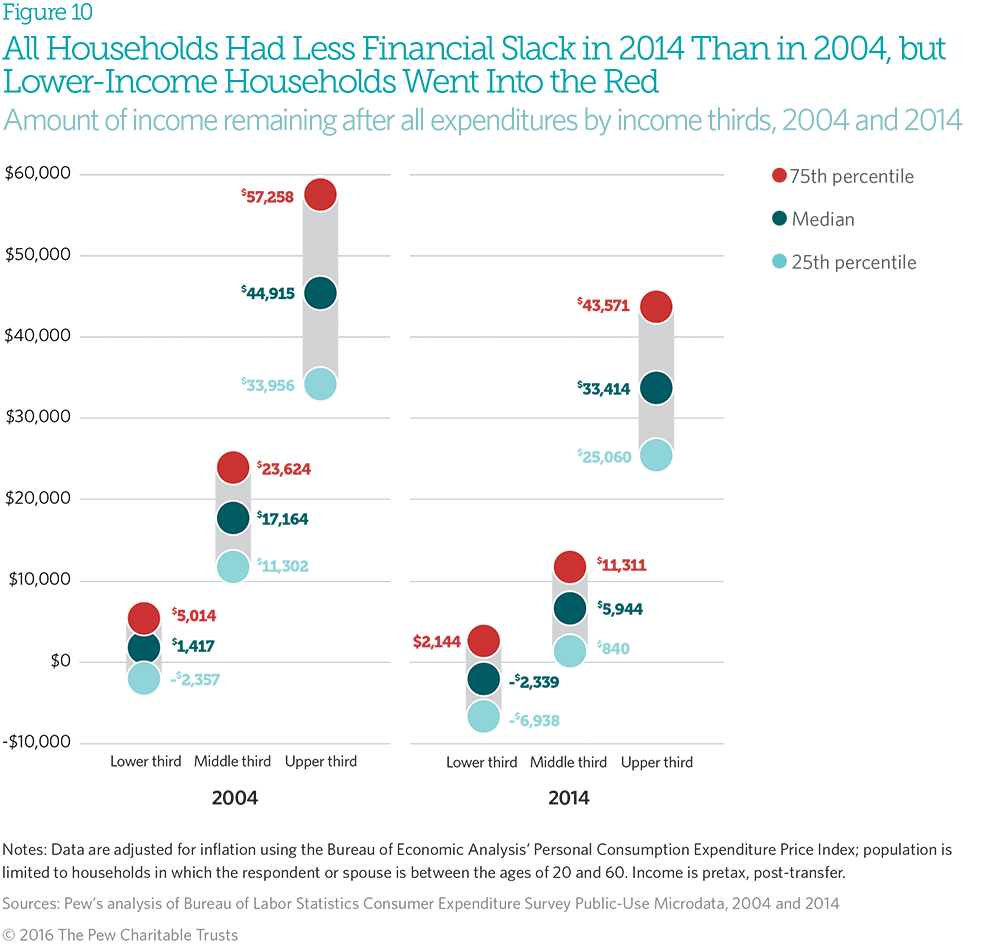

- Although all households had less slack in their budgets in 2022 than in 2004, lower-income households went into the cerise. In 2004, typical households at the bottom had $i,500 of income left over after expenses. By 2014, this figure had decreased past $3,800, putting them $two,300 in the blood-red. The lack of fiscal flexibility threatens low-income households' financial security in the short term and their economic mobility in the long term.

Households spent more than in 2022 than they did in 1996, after adjusting for inflation; this holds whether the figures are based on averages (means) or medians. The typical household saw its expenditures grow by more than than 25 percent, from $29,400 in 1996 to $36,800 in 2014. Mean expenditures grew 27 percent since 1996, rising from $43,200 to $54,800. Much of the growth occurred betwixt 2012 and 2014, signaling a promising recovery from the Great Recession and the housing crisis.

From 2004 to 2008, median household income grew past only 1.5 percent,iii while median expenditures increased past about 11 percentage. During that menses, the expenditure-to-income ratio (the percentage of a household's budget used for spending) jumped past nine percent. As the recovery began, median household expenditures returned to pre-crisis levels, but median household income connected to contract. By 2014, median income had fallen by 13 percent from 2004 levels, while expenditures had increased by nigh fourteen percent. This change in the expenditure-to-income ratio in the years post-obit the fiscal crisis is a clear indication of why and how households feel financially strained.

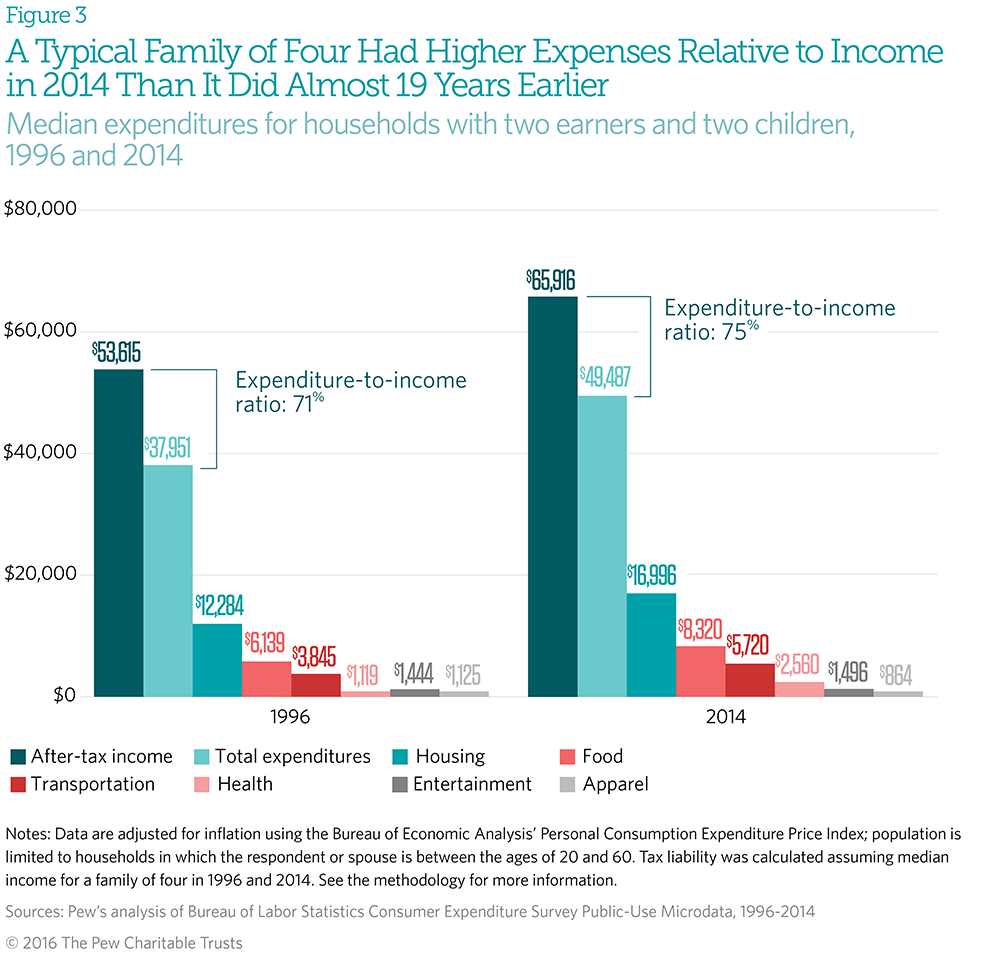

For a typical family of four (two earners and two children), while median household income increased past about $10,000 betwixt 1996 and 2014, annual expenditures besides increased by about the same amount, driven largely by college spending for core needs: housing, food, and transportation. Although the absolute change in income and expenditures was similar, this family had less slack in its budget in 2022 than in 1996, every bit its expenditure-to-income ratio grew from 71 percent to 75 percent.

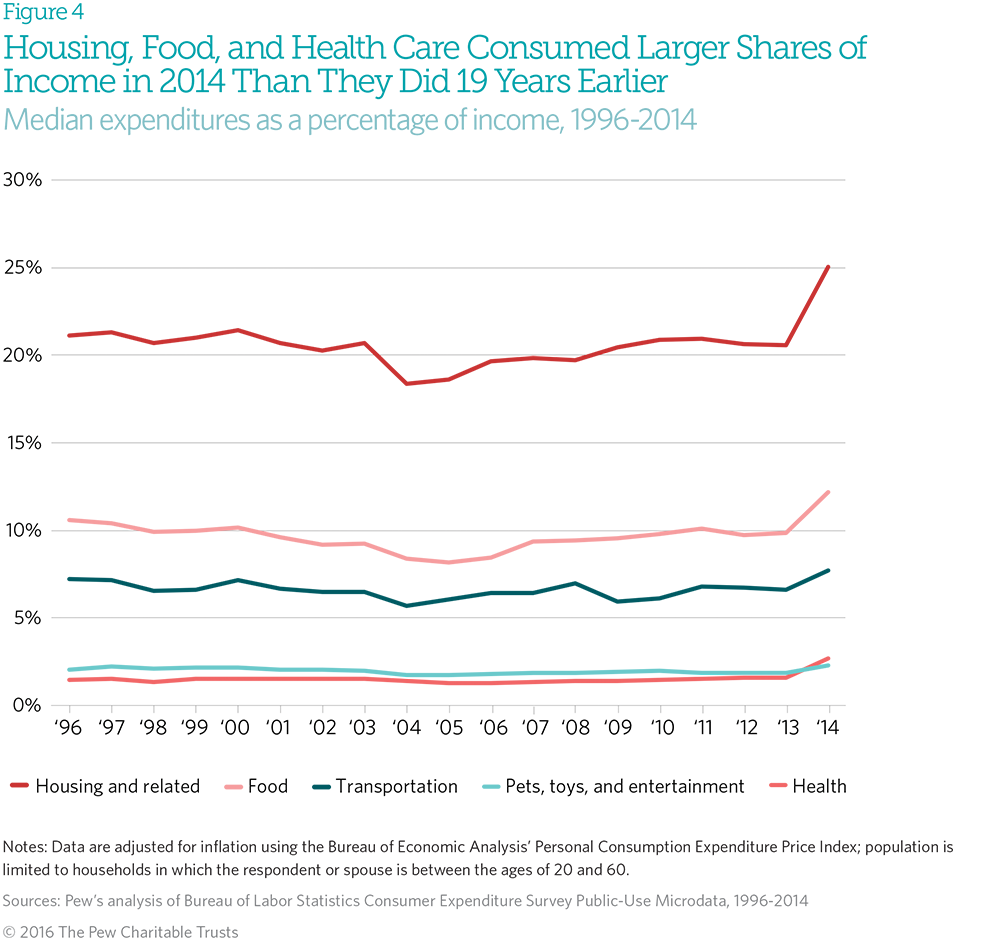

Near two-thirds of families' spending goes to core needs: housing, food, and transportation. In 2014, housing obligations accounted for the largest share of household pretax income, about 25 percent. Over the 19-year study menses, amass median housing expenditures absorbed 21 percent of families' pretax income. The second-largest expenditure, food, typically consumed nearly 10 percentage of family income, while transportation took 7 percent. The proportion of household spending that these categories account for has shifted very lilliputian over the past 2 decades.

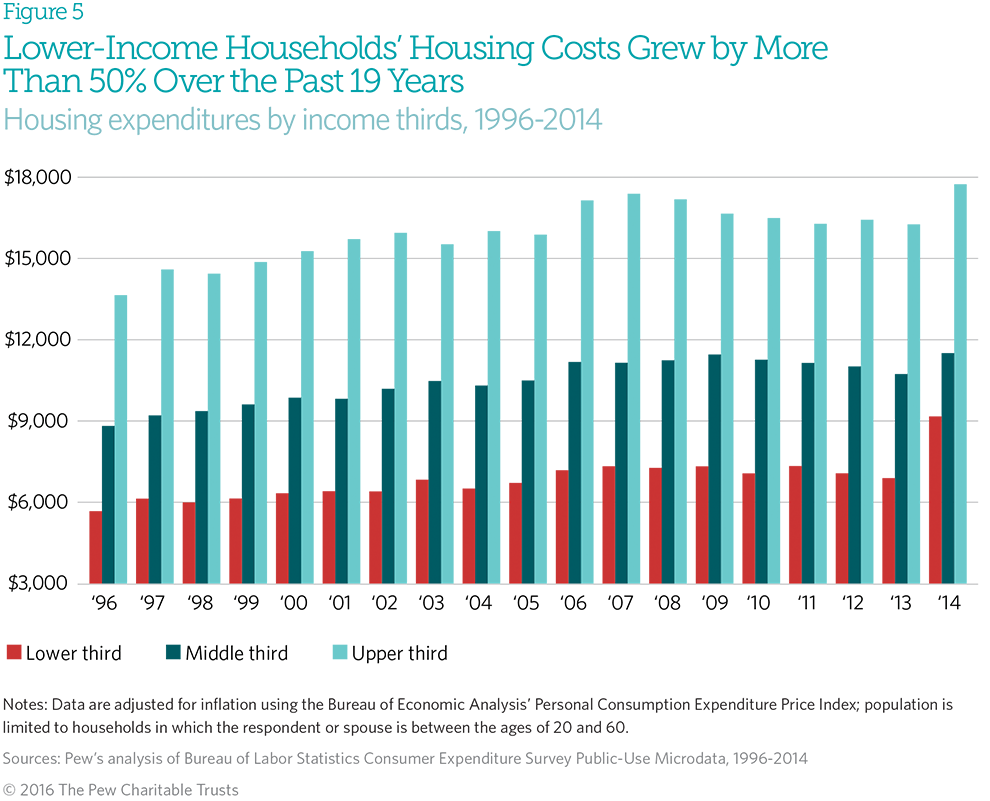

Over the past two decades, spending on housing increased for Americans in all income tiers. In 2014, households in the lower tertiary spent much less in accented dollar terms (most $nine,200) than those in the centre or upper thirds, whose median housing expenditures reached $11,500 and $18,000, respectively. However, the typical lower-income household spent far more on housing as a share of income (xl percent) than those in the middle (25 percent) or at the meridian (17 per centum).

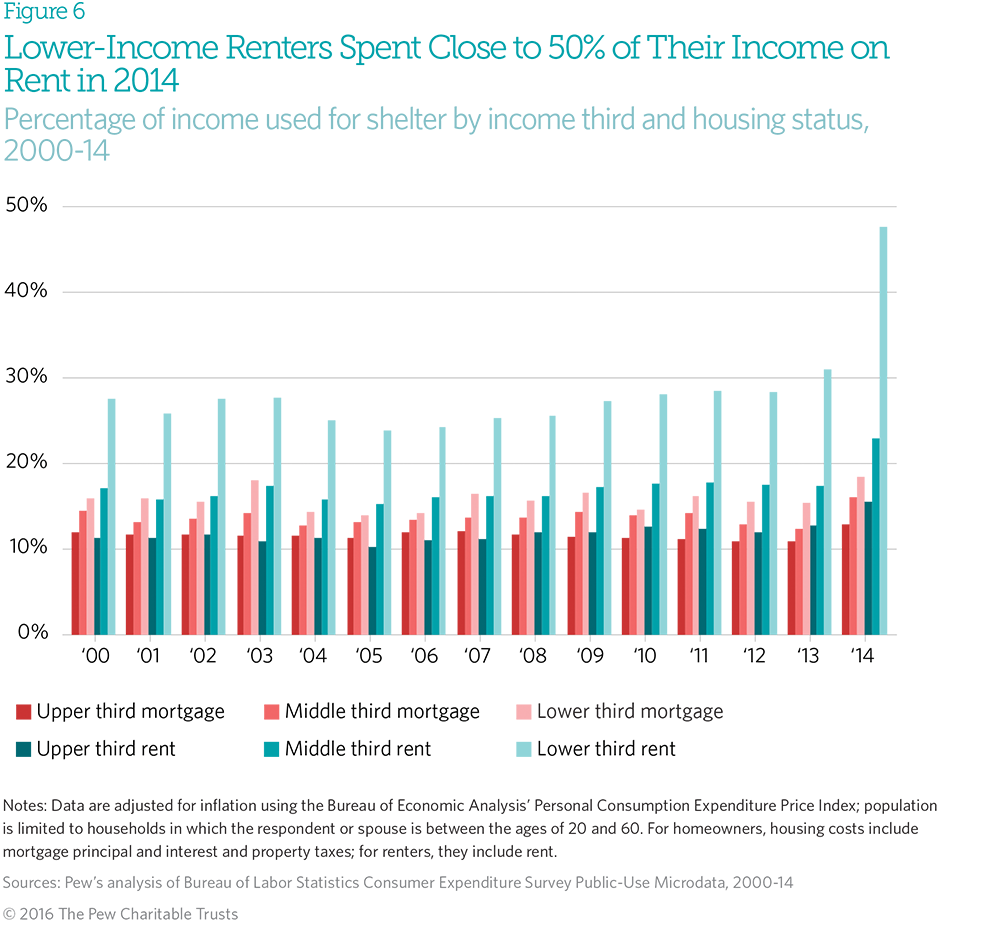

Since the beginning of the housing crisis in 2007, homeownership rates have declined among households in the eye- and upper-income tiers. These decreases accept affected the rental market place, equally former owners became renters, leading to rental vacancy rates at historical lows below seven pct.four The diminished supply of rental properties increased the cost of rental housing dramatically; in 2014, renters at each rung of the income ladder spent a college share of their income on housing than they had in any year since 2004. Although both renters and homeowners spent more for housing in 2014, notable differences in the proportion of household resource going to shelter were evident across income groups, with lower-income renter households spending close to half of their pretax income on rent.

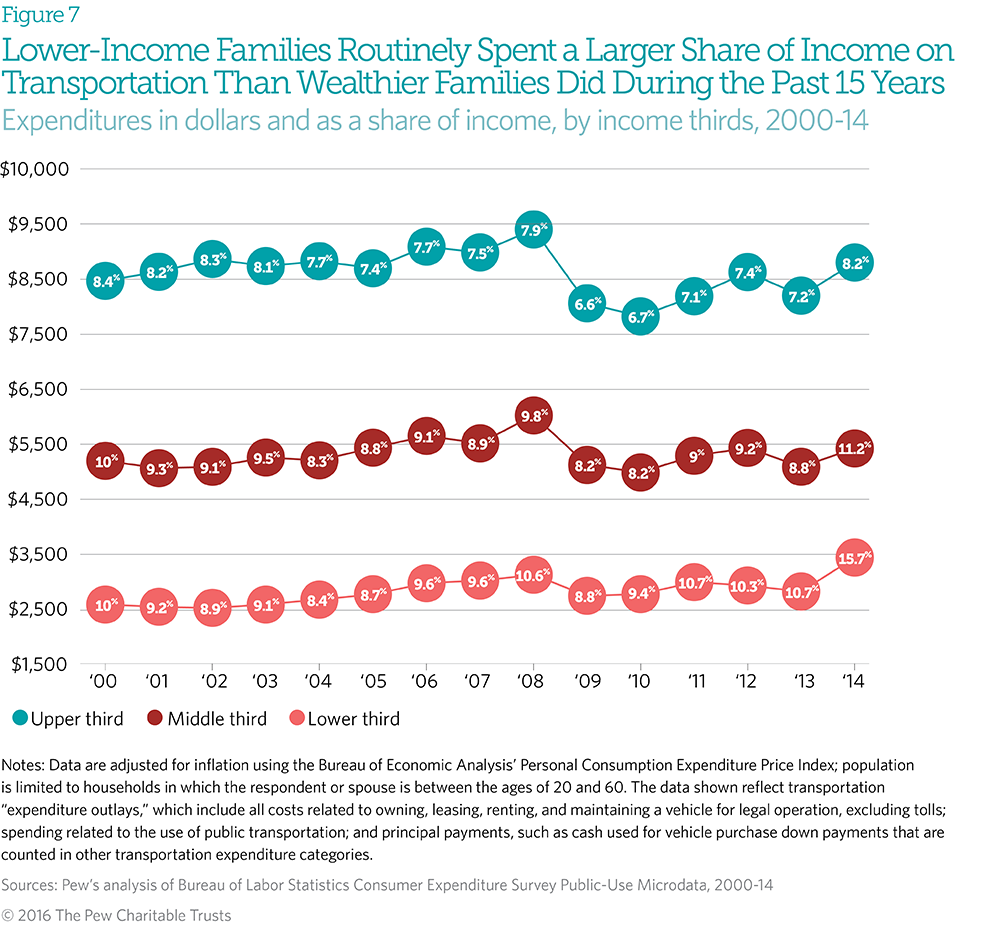

As with housing, households in the lower income group spend significantly less in absolute dollars, but much more equally a share of their income, on transportation than did those in the centre- or upper-income groups. Farther, transportation costs increased in recent years for households at the bottom, while this spending was more stable for the other income groups. Lower-income households spent most xvi percent of their income on transportation in 2014, up from 9 percentage iv years before. In contrast, households in the centre spent nearly eleven percent of their income on transportation in 2014, while those at the elevation spent 8 percentage.

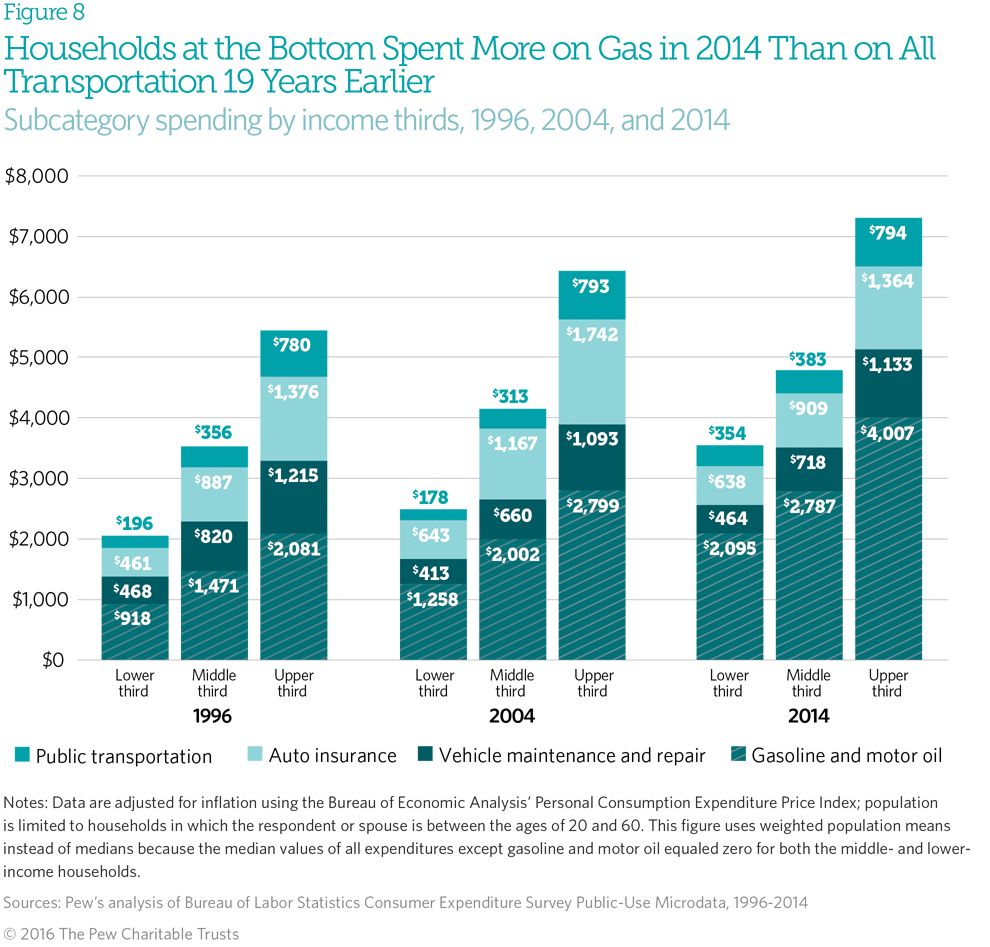

As the share of household income used for transportation increased, the amount going to various subcategories also grew. For all income groups, expenditures for gasoline and motor oil doubled between 1996 and 2014. For households in the lower third, the average annual cost of fuel, auto insurance, vehicle maintenance and repair, and public transportation in 1996 averaged $2,000 a year; past 2014, this group spent near $2,100 but on fuel. These extreme price increases strength households to make difficult choices and trade-offs to meet core needs.

Though systemic economic weather, such as recessions or stock market place changes, affect trends in consumer expenditures, individual households likewise make decisions about how to spend their discretionary dollars. In 2014, households across the income distribution spent much more on groceries than on eating out, just, predictably, those in the elevation tertiary spent much more on nutrient away from dwelling than the other groups. Households at the top also spent more than than others on entertainment, including pets and pet intendance, media equipment and services, admission to events such every bit movies or plays, and toys for children. Typical households at the pinnacle spent $380 a month on eating out and entertainment. Conversely, households in the lesser third, which had significantly less slack in their budgets, devoted very few resource to these two categories— about $128 a calendar month.

The corporeality of slack that families had in their budgets declined for all income groups between 2004 and 2014. This ways households had less income to devote to wealth-edifice investments, such as short- and long-term savings, education, and life insurance. In 2004, the typical household in the lower tertiary had a piddling less than $1,500 left over afterwards accounting for almanac outlays. Just 10 years later, this amount had fallen to negative $2,300, a $3,800 decline. These households may have had to employ savings, become aid from family and friends, or employ credit to meet regular annual household expenditures. The typical household in the middle third saw its slack driblet from $17,000 in 2004 to $6,000 in 2014. Of note, because income is measured before taxes, some families will accept had even less slack in their budgets than this figure implies.

Endnotes

- Walter Lake (2015), Kiwi & Cassava Version 3 [Estimator software], Washington, https://github.com/Kiwi-den-den/KIWI.git.

- This chartbook follows the lead of the Bureau of Labor Statistics in referring to consumer units interchangeably as households and families. However, not all consumer units are families. The BLS definition of a consumer unit is: "(1) All members of a particular household who are related past claret, marriage, adoption, or other legal arrangements; (2) a person living alone or sharing a household with others or living as a roomer in a private domicile or lodging business firm or in permanent living quarters in a hotel or motel, but who is financially independent; or (three) two or more persons living together who use their incomes to make joint expenditure decisions. Financial independence is determined by spending beliefs with regard to the three major expense categories: Housing, nutrient, and other living expenses. To be considered financially independent, the respondent must provide at least two of the three major expenditure categories, either entirely or in role."

- In 2004, the Consumer Expenditure Survey started to include income information produced using multiple imputations. This alter in methodology immune the BLS to better capture income information when the respondent did not provide or refused to provide information on one or more east sources of income. The result of the methodical change is an increase in household income, which may explicate in part the steep increase in income and the a.yard. decrease in the expenditure-to-income ratio. Some circumspection should be exercised when comparing income values before 2004 with those later on 2004. Even so, other nonrelated data sets, such every bit the U.S. Census Bureau'southward Table H-eight, Median Household Income past State: 1984 to 2014, also indicate that median household income increased by 2.three percent from 2003 to 2004 and by 6.ix percent from 2004 to 2005. Therefore, this analysis assumes that median household income did increment only that the magnitude of that growth indicated in the Consumer Expenditur e Survey may reflect a combination of the improved data collection methodology and the bodily increment.

- U.S. Demography Bureau, "Annual and Quarterly Charts of Rental and Homeowner Vacancy Ratn es and Homeownership Rates," accessed Oct. thirteen, 2015, http://www.census.gov/housing/hvs/information/charts.html.

Boosted RESOURCES

More FROM PEW

Source: https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/issue-briefs/2016/03/household-expenditures-and-income

0 Response to "Average Household Expenditures by Major Category Family of 4"

Post a Comment